The (Programming) Legend of John Henry

You Can’t Replace a Steel-Drivin’ Man

And what’s a substitute for bread and beans? I ain’t seen it! /

Do engines get rewarded for their steam?

...

John Henry said to his captain “A man ain’t nothin’ but a man /

But if you’ll bring that steamdrill ’round I’ll beat it fair and honest. /

I’ll die with my hammer in my hand but, but I’ll be laughin’, /

‘Cause you can’t replace a steel-drivin’ man.”

— Johnny Cash

From The Mythical Man-Month to the 10x programmer, to silver bullets and manifestos—there is no shortage of legends, folk tales, and founding myths in software engineering.

One such story, which has been on the top of my mind recently, is the legend of John Henry.

Now, the legend of John Henry does not fit neatly beside other programming stories, like, maybe, the Y2K bug, or Mark Zuckerberg’s battle against the Winklevoss twins, or the meeting of 17 tech visionaries on top of a mountain in Snowbird, Utah. No, no, this story predates Y2K by over a century, and as such, does not have its origins is software, like these other examples. But the story of John Henry does have its origin in technology.

I hate to compare programmers to railroad workers—I really do. But at the heart of John Henry’s story is a story about technology, and something I think we can all relate to today, to some degree, programmer or not.

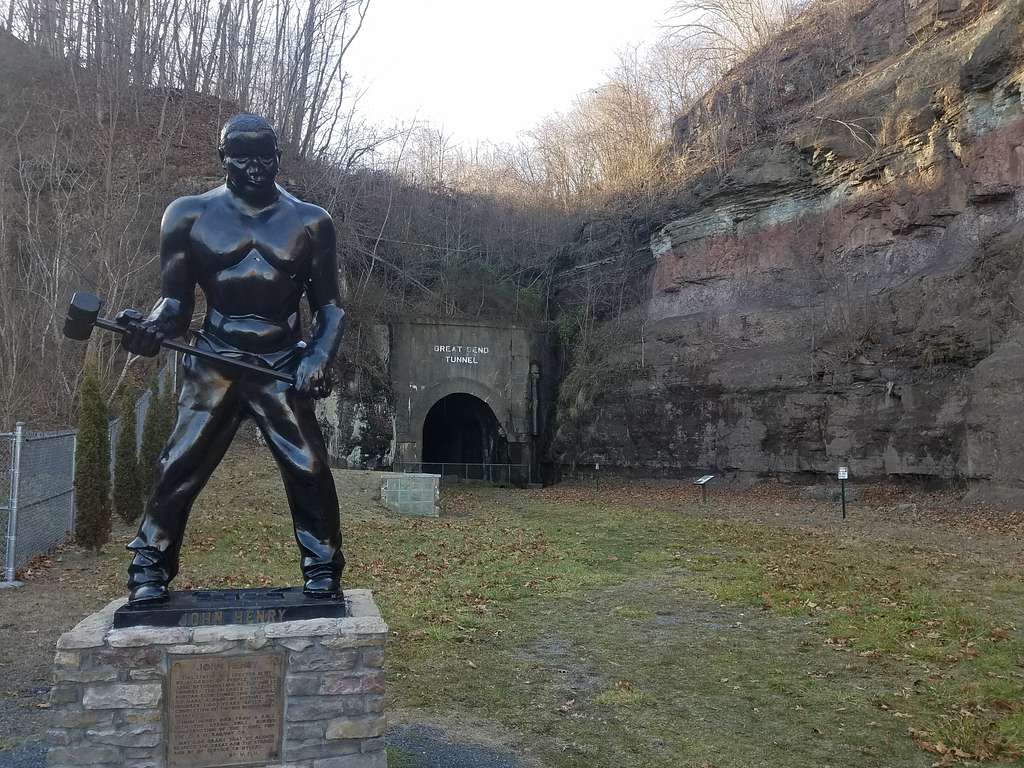

John Henry was a steel-drivin’ man, as the legend goes.

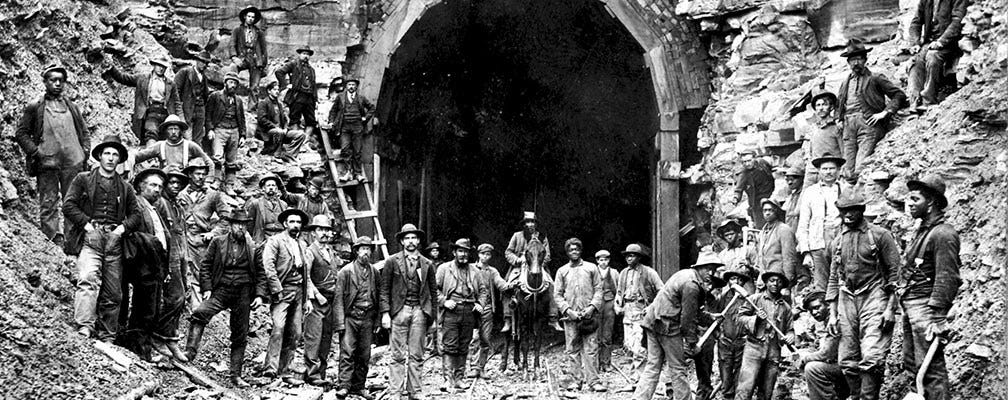

Stories of John Henry date back to the late 19th century, most likely having their origins in Appalachia, where the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad (C&O) forged its way through the coal-filled mountains of West Virginia.

From 1870 to 1872, Railroad workers worked tirelessly, digging a 1 mile-long (1.6 km) tunnel for the new C&O railroad. This tunnel would come to be named the Big Bend or Great Bend Tunnel, and today is decorated with a plaque and a statue honoring the labor of John Henry.

Like many folk stories and railroad songs, John Henry’s story is simple on its surface. But underneath, it depicts something much more complex—something almost intangible. It highlights feats of impossible physical strength, human skill, and perseverance, but it also serves as a warning.

This story lives on, primarily, in folk music, where it’s represented in a similarly complicated way, musically. Most versions of John Henry carry an upbeat tempo, and a positive-sounding melody—it’s only when you listen to the song’s lyrics that the whole picture becomes clear.

John Henry's captain he said, "I'm on a rock" /

He said, "I think this tunnel's falling in" /

Then John Henry smiled at his captain and he said /

"Now boss that's my hammer sucking wind, Lord, Lord /

Boss, that's my hammer sucking wind"

John Henry he had a sweet little woman /

Her namе was Polly Anne /

And while John he was sick and hе laid down on his bed /

Little Polly drove that steel like a man, Lord, Lord /

Polly drove that steel like a man /

John Henry hammered in the mountainside /

Till his hammer caught on fire /

And the last word that poor John Henry said /

"Give me a cool drink of water 'fore I die, Lord, Lord /

Cool drink of water 'fore I die" /

They took John Henry to the graveyard /

Six feet under the sand /

And every time a freight train would come a-rollin' by /

They say, "Yonder lies a steel-driven man, Lord, Lord /

Yonder lies a steel-driven man"

There’s another popular Appalachian folk song, from a similar time period, that comes to mind—a murder ballad, Tom Dooley. Tom Dooley is another example of an upbeat, positive-sounding song which does not sonically align with its dark, murder-ballad lyricism.

Maybe there’s something in the Appalachian spirit that inspires this tension between joy and sorrow, victory and defeat. Maybe it’s the landscape. Or perhaps it’s the history. The Appalachian Mountains are among the oldest mountain ranges in the world and their past is fraught with struggle and controversy. But whatever the source may be, it’s this tension that makes me believe John Henry is the perfect lens through which to explore the modern story of man vs. machine.

Well, you read the lyrics—you know how the story goes.

In the end, John Henry wins. He bests the steam-powered, steel-driving machine at its own game. But, at what cost? Well, it was a very, very high cost—the highest cost of all—his own life.

Technology, What Is It Good For?

In that moment, humanity and technology were at a crossroads. A railroad crossing, if you will (sorry). It wouldn't be long before engineers would build a better steel-driving machine—one which would bore through mountains more effectively than John Henry, or any man, before or since. But for that brief moment in time, John Henry was better. No, he was the best. He was the last line of defense—the last man standing in an encroaching wave of automation. (He was Gandalf holding back the Balrog—Hodor holding the door against the White Walkers.)

You can take what you will from the John Henry story, but one thing is for certain: humans are proud. We want to be the best, and we hate losing. I mean, we’ll even try and race a horse if someone says we can’t.

And after the wave of automation which took John Henry, how many other such waves have come since? Waves of our own making. I mean, we hate losing, but we’re beating ourselves here, aren’t we?

Now, taking a step back—I mean, really zooming way, way out here–what does technology do for us, anyway?

At its most basic, we might say that it brings us safety, and order out of chaos. Fire, maybe the most basic technology, brings us warmth, the ability to cook, and light which extends our day, enabling more socialization. Fire is an amazing technology—it's really the underpinning of human civilization. But, once our Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs are met, at its highest level, we might say that technology improves and enriches our lives.

But our technologies also have an impact on us. We use a shovel in order to dig a hole. But it also makes us stronger and gives us calloused hands.

Health

I could go into a whole thing, about remote work, and how I recently bought an exercise bike, and how living in rural America is strange; but, I’ll spare you the details.

I just want to be healthy. That’s basically it.

Mind, body, and soul.

But I don’t think that’s what we’re using technology for. At least, that hasn’t been my experience. We’re not using it to introduce more safety, or create order out of chaos. We’ve done that already, in a lot of areas, maybe even most areas. But now, we’re just… growing. It’s just more.

When it comes to computers and software in particular, it’s often the Jevons effect at work—

[W]hen technological advancements make a resource more efficient to use (thereby reducing the amount needed for a single application); however, as the cost of using the resource drops, if the price is highly elastic, this results in overall demand increasing, causing total resource consumption to rise. — Wikipedia

Now, I’m not trying to sound like a luddite. It just all feels a little bit “claustrophobic”. Maybe we should all just, ya know, slow down for a second? 😅

Maybe this is what John Henry felt. Is the wave that swallowed up John Henry coming for me, too? It feels like I’m on that water planet in Interstellar, with the water licking at my ankles. Can anyone else feel like that?

I guess what I’m arguing for is some semblance of balance. For example, I don’t like seeing that 70% of a blog’s traffic is from LLM web crawlers. It doesn’t sit right with me. There’s no regard for the common good there—it’s just more.

And, I’m not worried about AI taking my job, or “someone using AI” taking my job. In fact, I am really settling in to life as a programmer (re: exercise bike). But I am proceeding with caution, because I don’t know what sort of callouses an AI-driven software development world is going to give me.

But lo! Men have become the tools of their tools. The man who independently plucked the fruits when he was hungry is become a farmer; and he who stood under a tree for shelter, a housekeeper. We now no longer camp as for a night, but have settled down on earth and forgotten heaven. — Henry David Thoreau